“Uberization” is a catchphrase that has quickly become part of common parlance in discussions about the pandemic-induced economy. Uberization is the movement by organizations to “replace fixed wage contracts with ‘dynamic pricing’ for labor” (Davis, & Sinha, 2021). It is transforming many elements of the economy and replacing employees employed by the organization with a type of self-employed or contract employee. In essence, it allows businesses to “recruit labour at a large scale in new ways” (Davis, & Sinha, 2021).

The global business community has had a range of responses to the trend of uberization (Babali, 2019), as has the healthcare industry in particular. Yet as health systems emerge from the pandemic, Bloomberg reports that “the ongoing elevated costs of [healthcare] workers are causing profit warnings” (KHN, 2022; Court, & Coleman-Lochner, 2022). Regardless of one’s resistance or acceptance of uberization, healthcare employment is in crisis. Change must occur to keep health systems from financial disaster.

It seems that the tide of uberization in the healthcare industry is already rising. An increasing number of employees are contracting with hospitals and health systems via a staffing agency. This trend is likely to evolve, with a portion of staff employed directly by the hospital, and the remaining employees self-contracting with hospitals or health systems with short-term or even daily contracts. In fact, hospitals are reporting that rather than temporary “travel nurses” coming from other states to work on a contract basis, nurses are taking short-term contract work at hospitals a short drive from their own homes rather than pursue permanent employment with these organizations. We are witnessing the uberization of nursing, which will eventually extend to other healthcare occupations.

Why uberization?

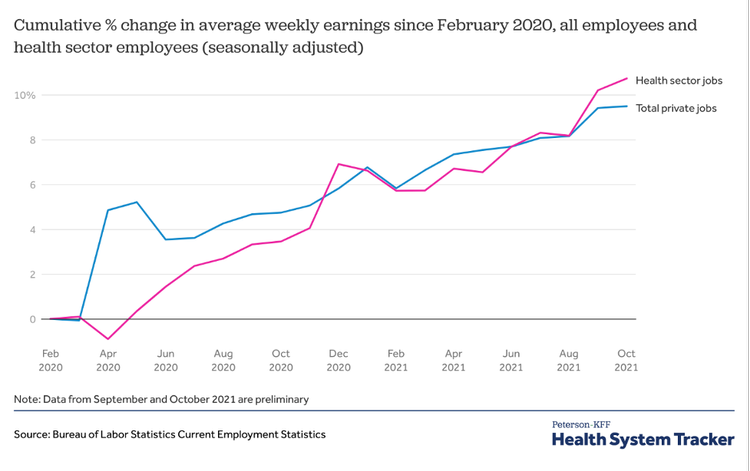

The healthcare workforce shouldered the heavy burden of fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet a collaborative study from Indiana University, the nonprofit Rand Corp., and the University of Michigan that analyzed the changes in the U.S. healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic found that “the average wages for U.S. healthcare workers rose less than wages in other industries during 2020 and the first six months of 2021” (Toler, 2022; Cantor, Whaley, Kosali, & Nguyen, 2022). According to a February 2022 report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, only about 35 percent of healthcare and social assistance organizations “increased wages and salaries, paid wage premiums, or provided bonuses because of the COVID-19 pandemic” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).

Due to the media attention the “Great Resignation” has received, it is common knowledge that workers across industries have been leaving their jobs at higher rates than before the pandemic (Parker, & Horowitz, 2022). Yet by October 2021, when the “quit rates” were at their highest recorded levels, healthcare and social assistance job resignations had increased to 35% higher than they had been before the pandemic, slightly higher than the increase of resignations among all workers in the same period (29%) (Wager, Amin, Cox, & Hughes-Cromwick, 2021).

Over the last ten years, “the salary of registered nurses increased by 1.67 percent in the United States” (Michas, 2021). Whereas healthcare executives make on average eight times more than their hourly employees (Saini, Garber, & Brownlee, 2022). The pandemic has rebalanced the scales in favor of those underpaid for many years. The salary landscape has changed, and in response many hospital systems blindly grasp to the pre-pandemic state of agency staffing. This, combined with near flat salary increases, contribute to the uberization of healthcare.

For many healthcare professionals, the combination of work-related stress and incommensurate compensation was the final straw. However, in addition to fair salary, flexibility has become a top demand of employees—even in healthcare. “Gone are the days when job security or pay was everything. Workers now are giving more thought to how their jobs fit into their lives. Ambition for ambition’s sake is being reassessed” (Buckingham, & Richardson, 2022).

A recent survey articulated “higher pay and dissatisfaction with management were also key drivers of nurses changing work settings in 2020 or 2021,” with 28% of respondents saying they’ve changed work settings (Lagasse, 2022). The percentage of nurses considering changing employers increased by 6% from 2020 to 2021, with 17% saying they are contemplating making an employment change. The percentage of nurses who are “passive job seekers – not actively looking for a new job but open to new opportunities – also increased, from 38% in 2020 to 47% in the current survey” (Lagasse, 2022).

The moment: contractor or non-contractor

As the trend of uberization continues to spread beyond the transportation industry, the global business community should be watchful of challenges that the trendsetter Uber is facing to understand future implications of this movement in their own industry. For example, recent legal battles regarding the employment status of Uber drivers will likely impact the cost-benefit analysis of those considering traditional employment or independent contracting. While an independent contractor is free to offer services to anyone and doesn’t have the limits on their freedom that comes with being an employee of a single organization, the U.S. National Labor Relations Board decision that Uber drivers are independent contractors means that drivers have no federal right to unionize (HyreCar, 2021; Fishman, 2020). In Europe, however, Uber drivers are considered employees and not independent, which could mean that unionization could occur en masse.

The future

The future of healthcare employment could be via an app on smart phones. Imagine: daily staffing supplemented by workers employed and credentialed through the app. The healthcare worker could choose their rate and shifts, and the hospital could determine the desired experience, quality, and patient experience reviews for the open position. It could shift the future of employment healthcare significantly.

The rate of change in today’s workplace is accelerating whether it is through the uberization of healthcare workers or advancements in workers’ rights. A recent New York Times article entitled “The Revolt of the College-Educated Working Class” states: “The support for labor unions among college graduates has increased from 55 percent in the late 1990s to around 70 percent in the last few years, and is even higher among younger college graduates” (Scheiber, 2022).

This may have a ripple effect on the healthcare workforce. Years of stagnating salaries and organizations’ undefined workforce vision has primed the industry for action with record job-quits within healthcare. This has proven especially true in rural markets where recruitment of permanent and agency staff has posed numerous challenges. Our current climate potentially opens the door for workers to leverage themselves via the advocacy of a union.

Summary

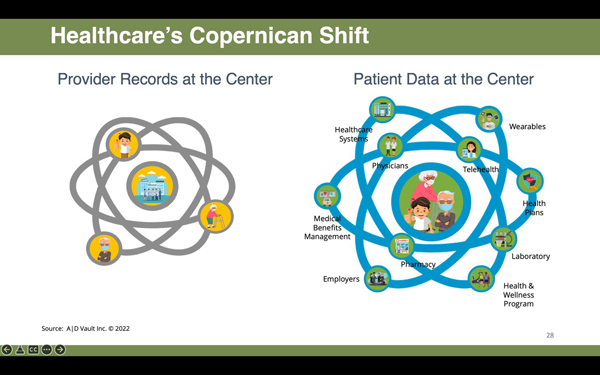

The labor supply and demand are out of balance. The long-term effects on the health sector labor market from the pandemic are unknown, but changes in healthcare delivery (such as the growth of telehealth) may lead to lasting shifts in the healthcare industry. Fierce competition for healthcare workers means that employers must go beyond good pay and benefits to attract the best candidates. Healthcare recruitment is a zero-sum game. There isn’t a pool of healthcare workers lying idle, and so recruitment is often at the cost of a competitor. The employee knows that this demand exists, and this could further drive the uberization of healthcare workers. However, there is potential for this new movement to benefit both parties. As limited number of employees equates to skill scarcity which drives salaries, hospitals could utilize their skilled workforce based on need and demand.

Resources

Babali, B. (2019). What is Uberization? The Business Year.

Buckingham, M., & Richardson, N. (2022). What’s Really Driving the ‘Great Resignation’. Barron’s.

Cantor, J., Whaley, C., Kosali, S., & Nguyen, T. (2022). US Health Care Workforce Changes During the First and Second Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(2):e215217.

Court, E., & Coleman-Lochner, L. (2022). ‘Unsustainable’ Squeeze Grips U.S. Hospitals on Covid Labor Cost. Bloomberg.

Davis, G., & Sinha, A. (2021). Varieties of Uberization: How technology and institutions change the organization(s) of late capitalism. Sage Journals, 2(1).

Fishman, S. (2020). Uber Drivers are Contractors Not Employees According to the NLRB. NOLO.

HyreCar (2021). Are Uber Drivers Employees or Independent Contractors: Explained. HyreCar

KHN (2022). Hospitals Losing Money, Thanks To Covid-Driven Cost Increases. KHN Morning Briefing, April 28, 2022.

Lagasse, J. (2022). Almost 30% of nurses are considering leaving the profession. Healthcare Finance News.

Michas, F. (2021). Average annual salary of registered nurses in the United States from 2011 to 2020. Statista.

Parker, K., & Horowitz, J. (2022). Majority of workers who quit a job in 2021 cite low pay, no opportunities for advancement, feeling disrespected. Pew Research Center.

Saini, V., Garber, J., & Brownlee, S. (2022). Nonprofit Hospital CEO Compensation: How Much Is Enough? Health Affairs.

Scheiber, N. (2022). The Revolt of the College-Educated Working Class. The New York Times.

Toler, A. (2022). Health care wage growth has lagged behind other industries, despite pandemic burden. Indiana University.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022). 24 percent of establishments increased pay or paid bonuses because of COVID-19 pandemic. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Wager, E., Amin, K., Cox, C., & Hughes-Cromwick, P. (2021). What impact has the coronavirus pandemic had on health employment? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker.

Leave A Comment